What happened to the ones that didn’t make it?

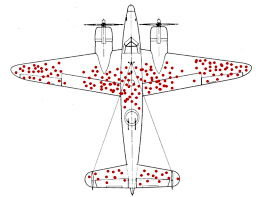

The image below has been widely shared on social media to demonstrate what is called survivorship bias:

In WW2 the airforce was trying to work out the best place to put armour plating to help planes survive. There was a balance to be struck between weight, speed and flight duration. To help the decision they looked at planes returning from raids to see where there were most bullet holes. The red dots on the diagram above summarise the results. They initially thought this was where the armour was needed, until someone pointed out that the right conclusion was exactly the opposite!

If we only consider the evidence from things that ‘survive’ we might be missing a big part of the picture. This article by David McRaney takes a more in depth look at this case and other aspects of survivorship bias.

What are the implications of this for economic development? When evaluating projects and programmes we, not surprisingly, have a tendency to look for best practice and what appears to work so we can transfer this knowledge to plans under development. Perhaps we should also be paying attention to what didn’t work and why.

Survivorship bias can lead us to think that things might be easier to achieve than they really are. As McRaney puts it:

Survivorship bias also flash freezes your brain into a state of ignorance from which you believe success is more common that it truly is and therefore you leap to the conclusion that it also must be easier to obtain. You develop a completely inaccurate assessment of reality thanks to a prejudice that grants the tiny number of survivors the privilege of representing the much larger group to which they originally belonged.

In appraisal this could link to optimism bias – how often do we overestimate the benefits of a project and underestimate they costs?

When looking at why something works or doesn’t, it is really important to consider the context in which it was tried and ask what unique circumstances might have been at play, which could be really hard to replicate elsewhere. The role of luck can’t be underestimated either.

Chance has long been seen as a key factor in the development of industrial clusters in certain areas. One of my favourite examples is the growth of the carpet industry in Dalton, Georgia, the seed for which was apparently a local craft fair at which one of the industry pioneers was inspired by a tufted bedspread he saw.

Scotland also has it’s examples. It has been said that the computer games industry in Dundee is founded on the skills of young software engineers who honed their skills on Sinclair home computers that found their way out of the local Timex factory where they were being made under subcontract. Others, such as Abertay University, spotted an opportunity to link local skills and talent with a growing marketplace and an industry cluster was nurtured.

Chance beginnings can set in train a process of circular and cumulative causation, as described by Gunnar Myrdal. When such a process takes hold an innovative, industry ecosystem of competitors, collaborators and specialist suppliers and institutions develops. This in turn generates agglomeration economies and network effects, which further spur growth. Conversely, if an area suffers a negative economic shock, a vicious downward spiral can result.

If chance can play such an important role in stimulating or holding back development, this begs the question of what place strategy? I’ve long been a fan of the apparently contradictory notion of ‘strategic opportunism’ whereby you have a clear idea of objectives and direction of travel but you are flexible enough to adapt to opportunities as they arise. Successful people and places may in part be, as McRaney puts it, be: ‘better at interacting with chance’.

It was interesting to note in the recently published ‘Delivering Economic Prosperity’ (Scotland’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation) that underpinning the vision, ambition and action programmes set out was a separate programme focused on delivering a culture of delivery. Effective co-operation and working across boundaries to achieve shared objectives quickly offers the opportunity to develop the flexibility to allow emerging opportunities to be grasped quickly/ This will require investment in strengthening and deepening the relationships between organisations and individuals to build the trust required to move beyond the transactional to become genuinely transformational.

It’s important to have a clear idea of where you want to get to, but it’s equally important (particularly for a relatively small country on the world stage) to be sufficiently fleet of foot to respond to changes in the environment in which you are travelling. Perhaps my father was onto something with one of his favourite phrases: ‘we’ll make a plan and then play it by ear’ – and he started working life as a navigator in the RAF, bringing us right back to where we started!

Charlie Woods, EDAS Vice Chair